It’s no longer science fiction. Artificial intelligence, the process of imitating human intelligence, is now part of our daily lives. But its ever-accelerating pace of development can be a cause for concern. Well-founded or not?

Movie fans will remember that, in the 1984 film Terminator, machines created by man turned against him and almost caused the annihilation of mankind. The programmed end of the human race caused by machines is a classic pop-culture fantasy. Does the advent of artificial intelligence make this age-old fear credible?

Photo credit: generation-nt

John McCarthy, who coined the term artificial intelligence, presents the concept as “the science and engineering of making intelligent machines”. Another AI specialist, Marvin Lee Minsky, describes it as “the construction of computer programs that perform tasks that are, for the moment, more satisfactorily accomplished by human beings”.

A long-standing fear of progress

Artificial intelligence crystallizes all the fears associated with technology and progress, which are nothing new. Progress, especially technical progress, has often given rise to doubts and anxieties. In the 19th century, during the Industrial Revolution, David Ricardo, one of the fathers of liberal economics, envisaged that machines could replace man. At the same time, in England and France, textile mill workers destroyed the machines intended to replace them.

Is it reasonable to imagine AI replacing or controlling the human species?

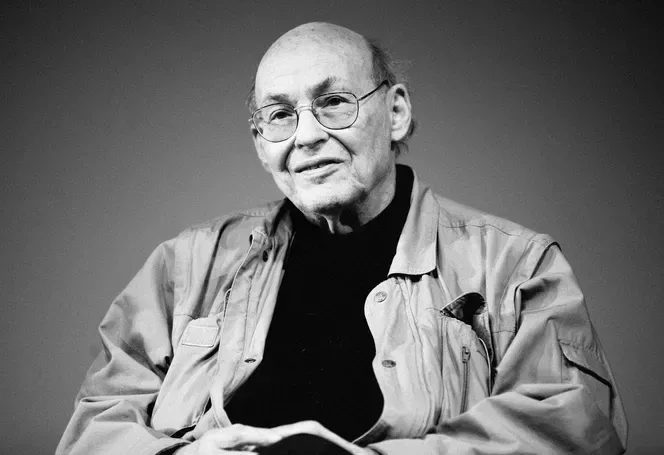

The speed with which artificial intelligence is advancing, notably with the recent arrival of ChatGPT, a conversational agent, makes one’s head spin. AI has made phenomenal progress,” admits Jean-Gabriel Ganascia, a French computer scientist, philosopher and artificial intelligence specialist, ” and its learning capacities can go very far. However, it’s impossible for AI to take over people’s lives, and they need to be reassured!

AI, nothing more than a high-performance computing tool?

Let’s reduce artificial intelligence to what it is, and not to what it emotionally arouses in our human brains: a calculation and data management tool. Its creator, the human being, teaches it to store and analyze colossal quantities of information. However, AI is no match for human intelligence. It has no feelings, no morals, no ability to feel emotions or to reason. The best proof of this is its propensity to relay fake news, which it will have collected in its memory without being able to analyze their relevance and veracity.

And therein lies the real threat of AI: the use that humans can make of it. A recent example is the appearance on the Internet of images generated by AI, but so realistic that some people can fall for them. These “faked” photos have been produced at the request of a human being, who, if his or her intentions are malicious, will create a harmful product. The solution would then be to impose a statement indicating that the visual has been generated by AI, and is not real.

AI, an opportunity to rethink our society

Faced with these excesses in the use of AI-related technologies, it’s up to our societies to regulate how we take advantage of this tool, which has been part of our lives for several years now: facial recognition, autonomous driving, navigation systems, voice assistants…

It is in the field of medicine that AI is making its most spectacular contribution, with the hope of designing more predictive and personalized medicine. In addition to these tried-and-tested applications, Jean-Gabriel Ganascia reminds us that AI enables us to question current societal issues: “Thanks to AI, we realize that we will no longer need to leave thankless, tedious tasks to humans,” he continues. This forces us to think differently about our relationship with work, which is once again at the heart of the debate on pensions. AI is no longer an enemy, but a tool that serves mankind. ” With AI, we can invent a new model for society.

To make AI a tool for social progress rather than a threat, it’s up to our societies and their leaders to be vigilant and, as with any super-powered technology, to educate people so as not to let algorithms reinforce discrimination or inequality, and to ensure the best possible sharing of tasks between humans and machines. In this way, we can almost make a liar out of Stephen Hawking, the theoretical physicist who mischievously decreed that AI could be “the best, but also the worst, of human history”.